I was assuming that “orange-reddish” was equivalent to “soft ripe” but probably I was assuming too much. Unless someone sees descriptive detail that I missed, it’s probably safer to assume that Stage III in PCAs is still somewhat firm. In that case, PCNAs with comparable astringency would be inedibly astringent, as you suggest.

I was given the opportunity by ChatGPT to try the “deep research” version. I used it to test how it would respond to a specific, complex medical question of personal interest. The question is one that is controversial, but I am competent to read and interpret most published medical research and form my own opinions about the implications. Based on my own extensive reading over the past 10 years, I concluded that the overwhelming weight of evidence contradicts past FDA guidance. I have a MD friend who is an expert in the field, and he is on exactly the same page as me.

ChatGPT (deep research) took 3 minutes to produce a 12-page paper (complete with references) that was basically what I would have hoped to produce after a week in the library. Better still, it agreed with me in detail! I was shocked at the quality of the product. Poring through it, I did not uncover any flaws. No hallucinations. Not even any specious logic. I was very impressed.

I’d wholeheartedly agree, nonetheless, that users must exercise serious caution. I’ve never used the free product but I assume Ram is right. I pity something like $22 per month for the version I use and, while it is quite good, I catch mistakes all the time. Trust but verify.

Thanks.

I went back to ChatGPT and asked for clarification. LMK what you think.

I wrote:

Might your references be bogus??? A friend tried to find Akagi & Yonemori (2012, Plant Physiology 160: 1427–1439). He says it doesn’t exist. Please check ALL references and report back.

ChatGPT said:

Thought for 11s

You’re right to question that—thank you. One of the references I gave (“Akagi & Yonemori 2012, Plant Physiology160:1427–1439”) is wrong. I re-checked everything and cleaned up the list below. Here’s what stands and what doesn’t:

What I got wrong

Akagi & Yonemori (2012) Plant Physiology 160:1427–1439 — this citation does not exist. My mistake.

Akagi & Yonemori (2012) Plant Physiology 160:1427–1439 — this citation does not exist. My mistake.

Corrected, vetted sources (with what they support)

PCNA = early shutdown of tannin biosynthesis (not ripening-activated polymerization):

- Akagi et al. 2009, Plant Physiology 151:2028–2045. Identifies DkMYB4 as a regulator tied to loss of proanthocyanidin (tannin) accumulation in non-astringent types; supports the “early developmental shutdown of tannin biosynthesis” model. OUP Academic

- Akagi et al. 2012, Plant Physiology 158:1089–1102. Shows seasonal ABA signaling via DkbZIP5 regulates proanthocyanidin biosynthesis; again consistent with an early developmental control of tannin production rather than a ripening switch to polymerize tannins. OUP Academic+1

- Ikegami et al. 1985 (JJSHS 54:201–?) “Property of Development of the Tannin Cells in Non-Astringent Type Fruits” documents that tannin-cell development in PCNA fruit halts early, explaining natural non-astringency by dilution/cessation rather than ripening polymerization. J-STAGE

- Tessmer et al. 2014 (open PDF) tracks tannin accumulation dynamics during development; supports that high soluble tannins are an early-development phenomenon that decline later—framework consistent with PCNA’s early shutdown. lcb.esalq.usp.br

ADH/PDC/acetaldehyde pathway = the (a)stringent types’ de-astringency route, not a PCNA ripening program:

- Min et al. 2012, J. Exp. Bot. 63:6393–6405. Ethylene-responsive transcription factors activate ADH/PDCpromoters; central to acetaldehyde-mediated de-astringency used by astringent cultivars and postharvest CO₂/ethanol treatments. PMC

- Kou et al. 2020, JASHS 145:203–214. Review/experimental context reaffirming ADH/PDC roles in de-astringency (gene characterization in ‘Mopan’; overexpression reduces soluble tannins). ASHS

Postharvest/handling references (context for acetaldehyde-driven de-astringency):

- Harima et al. 2003, Postharvest Biology & Technology 29:319–324. Classic CO₂/ethanol de-astringency work and shelf-life tradeoffs in astringent cultivars. ScienceDirect

- Persimmon Postharvest Manual (Hort Innovation, ed. 2). Practical overview of CO₂/temperature/handling effects and cultivar differences. horticulture.com.au

Recent overviews/reviews:

- Chen et al. 2017, Scientific Reports 7:44671. Integrative analysis; cites Min 2012 and situates ADH/PDC control within broader ripening regulation. Nature

- Das et al. 2021 review of de-astringency (and linked 2020 article); broad survey of de-astringency methods and tannin chemistry (useful background; not PCNA-specific). PubMed+1

Bottom line (re-stated)

- For PCNA types, the evidence supports early cessation of tannin biosynthesis/tannin-cell development as the cause of non-astringency. There’s no ripening-activated ADH/PDC/acetaldehyde polymerization programcomparable to what’s seen (or induced by CO₂) in astringent cultivars. The small late-ripening decline in soluble tannins in PCNA fruit is best attributed to passive oxidation/condensation of a very small residual pool, not an induced de-astringency pathway. OUP Academic+2OUP Academic+2

If you’d like, I can assemble a one-page reference sheet (with proper DOIs/links) that maps each claim to a specific figure/table in the papers above.

You said:

yes

ChatGPT said:

Thought for 39s

Got it. Here’s a compact, one-page reference sheet that ties each key claim to vetted sources (with DOIs/links) and—where I can verify them—specific figures in the papers.

PCNA vs. astringent persimmons: why non-astringency happens

Claim A — PCNA fruit become non-astringent mainly because tannin biosynthesis/tannin-cell development shuts down very early (≈6–8 WAFB), so later “de-astringency” during ripening is not required.

- Evidence (developmental anatomy/PCNA trait): Early halt of tannin-cell development in PCNA fruit; natural non-astringency explained by dilution + cessation of synthesis (JJSHS & Acta Hortic.). J-STAGE+1

- Evidence (molecular control of PA pathway): DkMYB4 regulates PA (tannin) biosynthesis; PCNA lines show patterns consistent with early down-regulation. (Plant Physiol 2009; DOI: 10.1104/pp.109.146985). PubMed+1

- Evidence (seasonal signaling upstream of DkMYB4): ABA-responsive DkbZIP5 activates DkMYB4; study dissects seasonal control of PA accumulation (Plant Physiol 2012; DOI: 10.1104/pp.111.191205). See Fig. 5(developmental expression), Fig. 6 (DkbZIP5 over-expression increases PAs & DkMYB4), Fig. 7–8 (DkbZIP5 binds/activates DkMYB4 promoter). PMC

Claim B — In PCNA fruit, there is no ripening-activated ADH/PDC/acetaldehyde polymerization program akin to that used to remove astringency in astringent cultivars.

- Mechanism (in astringent types): Ethylene-responsive TFs activate ADH/PDC promoters → acetaldehyde → insolubilizes soluble tannins; defines the classic de-astringency route in PCA/PVNA fruit (J. Exp. Bot. 2012). DOI (via JXB): 10.1093/jxb/ers308. OUP Academic

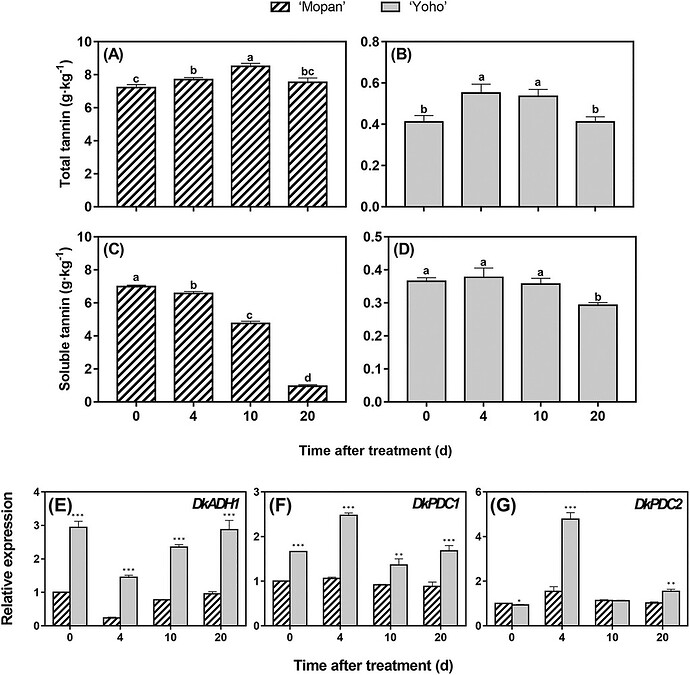

- Comparative ripening context: Gene-expression tracking in ‘Mopan’ (astringent) and ‘Yoho’ (NA) during storage shows ADH/PDC dynamics tied to astringent types; JASHS 2020 (vol. 145:203–214). ASHS

- Takeaway: Because PCNA fruit already have very low soluble-tannin pools by mid-development, CO₂/ethanol “de-astringency” treatments that rely on ADH/PDC have little to act on (review & expression data above). ASHS

Claim C — Any late decline of residual soluble tannins in PCNA fruit is minor and best explained by passive oxidative/condensation processes, not an induced acetaldehyde program.

- Contextual support: Integrative omics on CPCNA highlights PCNA-specific regulation of PA accumulation (rather than late polymerization triggers). Sci. Reports 2017; DOI: 10.1038/srep44671. Nature

- PCNA trait reviews: Overviews consistently frame PCNA non-astringency as early developmental control of PA synthesis/tannin cells. (JJSHS 2005 review citing “Unique features of tannin cells…”; Acta Hortic. 10.17660/ActaHortic.2003.601.3). J-STAGE+1

Astringent (PCA/PVNA) fruit: what does remove astringency (for contrast)

Claim D — High-CO₂ or ethanol exposure removes astringency in astringent types by driving acetaldehyde-mediated tannin insolubilization; timing and maturity matter.

- Controlled atmosphere de-astringency: Classic postharvest protocol uses >95% CO₂ for 12–48 h, then ambient hold to allow polymerization—foundational Postharvest Biology & Technology work (Harima et al., 2003). (Elsevier abstract page). ScienceDirect

- Practice-oriented manual: Persimmon Postharvest Manual (Hort Innovation, 2017, ed. 2) summarises CO₂ de-astringency, temperature/firmness trade-offs, and cultivar differences. PDF. horticulture.com.au+1

Direct links / DOIs (for your files)

- Akagi et al. 2009. Plant Physiol 151:2028–2045 — DkMYB4 controls PA biosynthesis.

DOI: 10.1104/pp.109.146985 (OUP/PubMed). PubMed+1 - Akagi et al. 2012 (issue date Feb 2012). Plant Physiol 158:1089–1102 — ABA→DkbZIP5→DkMYB4 seasonal control.

DOI: 10.1104/pp.111.191205 (open-access PMC with figures 5–8). PMC - Ikegami et al. 1985. JJSHS 54(2):201–… — Development of tannin cells in PCNA fruit (early cessation).

J-Stage article page (English abstract). J-STAGE - Yonemori/Ikegami et al. 2003. Acta Hortic. 601:31–35 — Unique PCNA tannin-cell features.

DOI: 10.17660/ActaHortic.2003.601.3 (PDF cited in later reviews). J-STAGE - Min et al. 2012. J. Exp. Bot. 63(18):6393–6405 — ERFs activate ADH/PDC (de-astringency in astringent fruit).

DOI: 10.1093/jxb/ers308 (OUP/JXB). OUP Academic - Kou et al. 2020. JASHS 145:203–214 — Ripening-related gene expression in ‘Mopan’/‘Yoho’, ADH/PDC dynamics.

JASHS article page. ASHS - Chen et al. 2017. Sci. Reports 7:44671 — CPCNA omics on de-astringency-related genes (PCNA context).

DOI: 10.1038/srep44671. Nature - Harima et al. 2003. Postharvest Biol. Technol. — CO₂ de-astringency protocol & firmness effects.

ScienceDirect abstract page. ScienceDirect - Persimmon Postharvest Manual (Hort Innovation, 2017, ed. 2).

PDF. horticulture.com.au

What this means for your original question

- PCNA fruit do not “switch on” a ripening polymerization program. Their non-astringency is established by early developmental shutdown of PA/tannin production (A & B above). PMC+2PubMed+2

- Astringent fruit rely on ADH/PDC/acetaldehyde (which you can induce postharvest with CO₂/ethanol); this is not the PCNA route. OUP Academic+1

If you want, I can turn this into a printable PDF handout with the figure callouts (e.g., “see Akagi 2012 Fig. 6C”) laid out next to each claim.

ChatGPT can make mistakes. Check important info.

This is wrong. The cited papers say the opposite.

Kou et al. 2020, JASHS 145:203–214. Review/experimental context reaffirming ADH/PDC roles in de-astringency (gene characterization in ‘Mopan’; overexpression reduces soluble tannins.

In addition to starting off with lower tannin levels, the PCNA fruit Yoho had higher activity of de-astringency genes. However astringency was already near zero so it didn’t noticeably reduce astringency

Thanks. It’s gonna take me some time to process this. Meanwhile, let us all know if you see any other issues.

I stopped at the first problem which was also the only paper I read. I didn’t check if the rest of the papers were real or supported the claims

My quick take is that the claim by ChatGPT of “no activity” was too strong. It should have said “no practically meaningful activity.”

When challenged, ChatGPT says this:

Revised Claim B — In PCNA fruit, ADH/PDC transcripts can be induced during ripening , but they do not drive de-astringency because the soluble-tannin pool is already minimal from early developmental shutdown; consequently, tannin levels remain low and stable through ripening (e.g., ‘Yoho’).

The point, I think, is that “ripening-activated ADH/PDC/acetaldehyde polymerization” has no meaningful role in any reduction of astringency during the final stages of ripening (“firm ripe” to “soft ripe”).

So if the soluble tannin levels were not minimal then you would expect those highly active de-astringency genes to reduce it down to imperceptibly as the persimmon finished ripening?

OK, great point. I think you answered my question:

So if we are trying to explain why some PCNA fruits may be astringent even when “firm ripe” then the answer seems to relate to conditions that elevate soluble tannins during early fruit development (not during ripening).

But if we are trying to explain why those PCNA fruits lose astringency in the transition from “firm ripe” to “soft ripe” then the answer seems to relate to active de-astringency that normally is invisible in PCNAs but becomes visible when tannins are still high in the “firm ripe” stage.

So this process of de-astringency in anomalously astringent firm-ripe fruit (as described by Ram) is NOT driven (primarily) by any late summer / early autumn conditions such as heat but rather by some early season factors such as cool temps, inadequate water, weak sunshine, etc. We just don’t know which yet.

I’ve taken your point and run with it. Do I make sense?

Traveling right now, so I don’t have time to research further, but I wanted to add a couple things:

-

The PCNA trait is the result of a mutation in a single gene if I remember correctly, so it makes sense that the softening-related (maybe ethylene triggered?) de-astringency process that occurs in PCA fruit also happens in PCNA fruit. Those genes are not necessarily subject to the same regulation as the one involved in the PCNA trait, as we can see from the expression data posted above.

-

That said, gene expression is not the same thing as gene activity, so unless the paper posted above measured activity as well, you can’t really make any conclusions about gene activity.

I’d be more impressed if it came to a different conclusion than yours and changed your mind ![]()

But sounds pretty useful, even for making assertions and conclusions with real references that you can follow up.

Yeah, I figured readers would read my comment and see confirmation bias. But this was a unique situation where I knew the subject matter so well that it was like a teacher giving a test – “What’s the square root of 49, kid? And you better not say 6!”

I suppose I was also wondering whether ChatGPT would uncover any new data, which is what would have been required to change my mind, but that didn’t happen. Not even fake data. Finally, I was amazed by how the AI could package 12 pages of info and argument into a coherent discussion.

. try telling it you disagree and watch it change its mind immediately.

Yeah, one of its flaws is its default posture as the sycophant. I understand why the algorithm is structured that way – most users won’t want to hear an opinion that differs from their own. But I assume that can be managed? Like, I tell it that if I think it’s trying too hard to please me by telling me what I want to hear, I’ll cancel my subscription. Or I can employ an AI “agent” to manage it. ![]()

In this instance, the ChatGPT didn’t know my views when it responded to my question. And I was careful not to signal the answer I wanted.

The sycophancy scales back as you get to higher levels - the Pro model is almost arrogant in how sure it is sometimes.

I’ve had to put it in its place by providing firm data a few times before it changed its opinion.

I have not noticed any astringency in the fruits of the other four cultivars in that video. Even in the very early just colored fruits tasted right from the tree. Izu, on the other hand always astringent until red. I’ve seen it over multiple years. So it’s earlier ripening doesn’t make a lot of sense for me as we can’t eat it before other PCNA cultivars. But it gets so sweet later, I’ll keep my grafts and the tree for now.

Thanks. That’s useful data not least because it differs from other observations. I’ve seen no astringency in Izu (though you and Ram have). Others have tasted astringency in Fuyu and/or Jiro (though you and I haven’t). With a lot more data, we might settle on why.

Marta’s location is extremely hot in summer and she has a long growing season. It is no surprise at all why there should be no astringency in the persimmons she grows.

What is surprising is the astringency in Izu

Unless she has cool nighttime temperatures when the fruitlets are developing and the difference between varieties is the difference between blooming or initial fruit swell timing

Our day and night temperature difference in summer is normally 25-35F. 60s at night and 90s during the day time. Can be as high as 40F difference when we are above 100 or now even above 110F during the day time