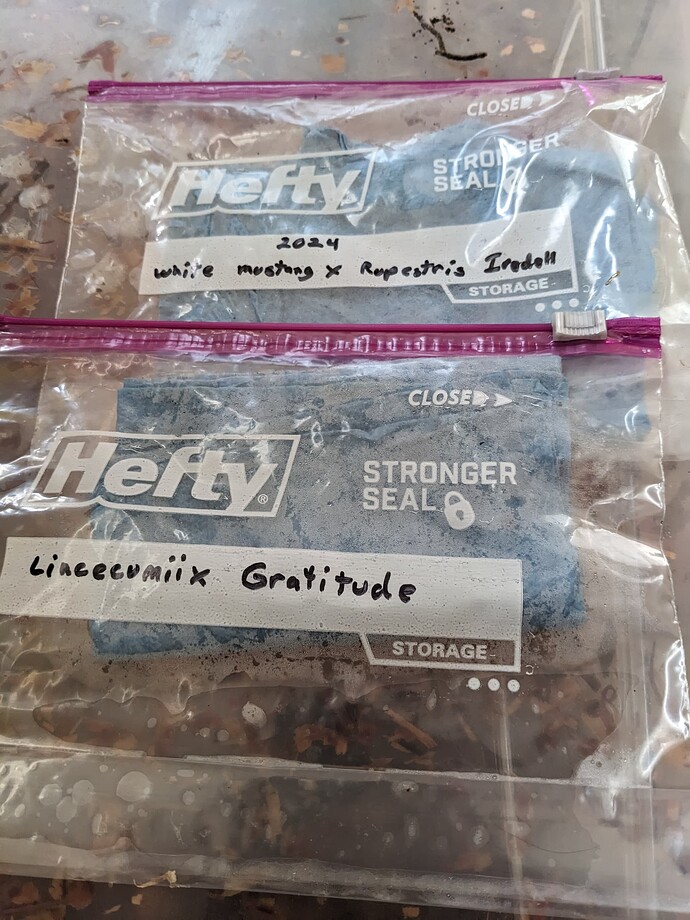

I looked in the archives and didn’t see anything similar to what I have in mind, so I thought I would create a thread about how to breed grapes & make crosses for interested amateurs. I first started growing grapes around 2008 & made my first crosses around 2012, and have continued with it every season since, making progress slowly and steadily, the way it happens in much breeding work. I am breeding for the climate conditions of the southeastern USA so my personal focus is on integration of disease resistance from wild sources into cultivated material. I hope this thread will provide encouragement and “how to” info for any grower who would like to try their hand at breeding but doesn’t know how to start. Anyone with a little space can breed grapes, the concepts are not difficult. It just takes interest, a goal, knowledge of material that possess the traits you want, and of course time. Of course any questions are welcome.

To start with, it’s helpful for the prospective hobbyist breeder to know a few facts about grapes.

-

Bunch grapes(which is everything but muscadines)are a diploid, 38 chromosome species. As a general rule, all 38 chromosome bunch grape species are fully cross compatible with each other and can pollinate each other and produce fertile offspring. This covers the majority of grapes. Muscadines are the exception. They are a more distantly related, diploid, 40 chromosome species and do not interbreed easily with bunch grapes due to the chromosome difference. It is possible to hybridize bunch grapes and muscadines with effort, particularly when the bunch grape is used as the female parent, but most offspring will have 39 chromosomes and be highly, or completely sterile. Like a mule. With enough effort, some slightly fertile hybrids can be found, and with back crossing fertility can be restored. This is how seedlessness was introgressed into muscadine varieties such as “razzmatazz” and “oh my”, but it take a huge amount of time and effort to do this successfully.

-

Grapes come with three possible flower types. Each unique vine/genotype will typically produce only one type of flower, and it will be the same every season.

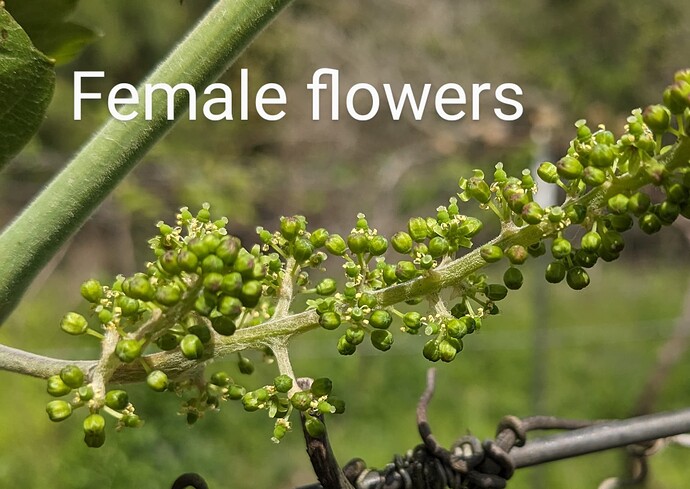

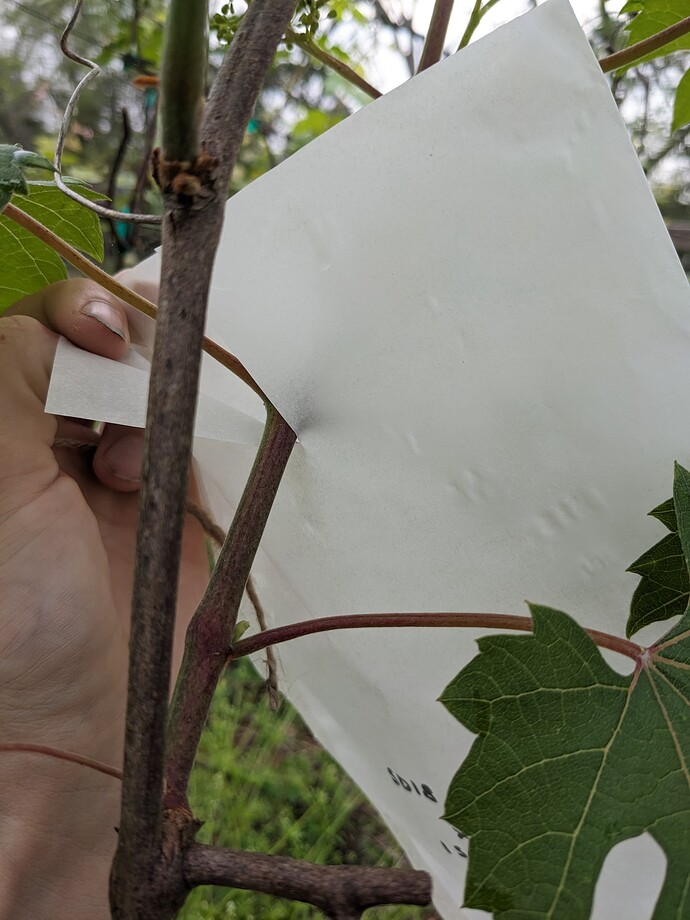

First you have female flowers. Female flowers have fully formed and fertile pistils, but short, curved/twisted anthers and the pollen is infertile. Female varieties cannot be used as a pollen parent, but are the most simple varieties to use as a seed parent, since they cannot self pollinate. All that is required is to bag the flowers clusters prior to bloom to protect them from stray pollen from undesired parents, apply pollen from the desired pollen donor to the bagged cluster during bloom, and rebag till the fruit forms. As easy as it gets.

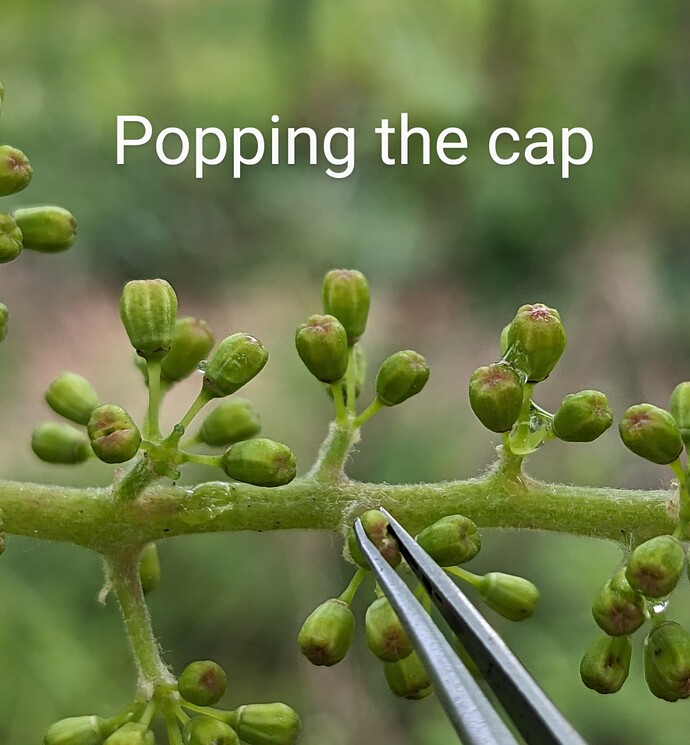

Next you have Perfect flowered varieties. Perfect flowered varieties have a fully formed and fertile pistil like a female variety, but unlike a female, they also have erect, straight stamens, and will produce viable pollen that is capable of both self fertilization, and of pollinating fertile pistils on other vines. As a result, perfect flowered vines can be used as either the pollen parent or the seed parent in breeding. This flower type is the type found in the majority of cultivated varieties, and is the most desirable flower type for most purposes.

Lastly you have male flowers. Male flowers are typically only found in wild material or rootstocks. Male flowers will have erect stamens and produce abundant pollen, but there will typically be no pistil present at all, or at most, a slight, underdeveloped and unviable indication of the beginning of a pistil. Because they have no pistil, these vines will bloom heavily but set no fruit. Typically this flower type is the least desirable to use in breeding, because roughly half of the offspring will also be fruitless males in any cross. The exception would be if you are working with rootstocks and fruit production is not a goal.

I think that’s enough for a first post in the thread. The next post will be on emasculating perfect flowered varieties so they can be used as a seed parent in breeding.