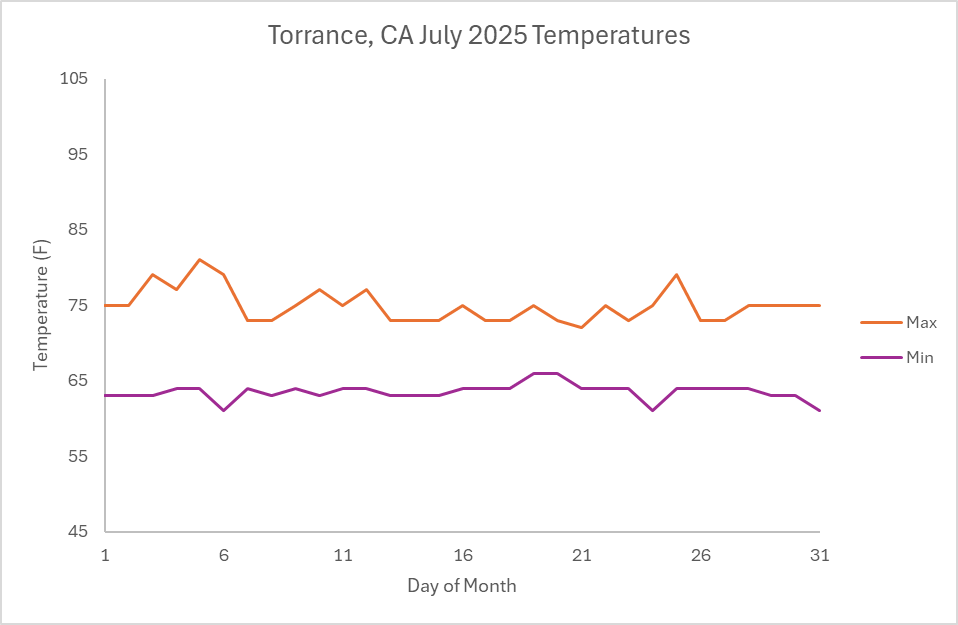

In the Persimmons 2025 thread, various views have been presented about residual astringency in ripe PCNA persimmons. One statement attributed to a Japanese grower implies that PCNAs cannot be grown in Japan much north of Tokyo, where the climate is subtropical. Another statement by a Taiwanese grower asserts that residual astringency can be tasted in PCNAs grown in some unspecified Middle Atlantic states (NY, NJ, Delaware, PA, MD, VA, WV) in the U.S, which are mostly not sub-tropical. A third statement from a grower in the Pacific Northwest says that it is impossible to grow PCNA’s anywhere where the climate is not “hot.”

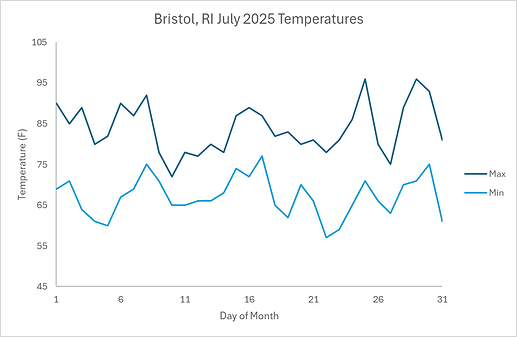

For my part, I have apparent success growing PCNAs in coastal RI. I’m gonna keep on, but I don’t want to see other growers give up on the idea of growing PCNAs north of the Mason-Dixon Line. But to settle the issue, we need more data.

If you have grown PCNA persimmons north of 39 degreed north latitude, please relate your experience – success or failure. Did you manage to ripen non-astringent fruit? Routinely? Did it matter whether the fruit was eaten firm or soft? Did you taste any astringency at all? Did this result vary by variety? And anything else you may think relevant. Thanks!